As a writer and English teacher, I want my writing to be perfect. Many of our students want the same thing. We all want what we see or hear in our heads to be exactly what we put onto paper, and this is doubly true for the writing we put online for the entire world to see. Try as we might though, our writing often doesn’t always appear on the paper (and especially not on the screen) the way we see it in our heads.

Unfortunately, some critics aren’t very forgiving. In the words of An Essay on Criticism by Alexander Pope:

‘Tis hard to say, if greater want of skill

Appear in writing or in judging ill;

But of the two less dangerous is the offense

To tire our patience than mislead our sense.

Despite the disdain of the referenced critics, writers are not dumb or unqualified because they make errors, even if those errors appear on the internet. Tom Stafford, a psychologist who studied typos at the University of Sheffield in the United Kingdom, explains the psychology behind grammatical errors to a Wired.com author:

Typos suck. They are saboteurs, undermining your intent, causing your resume to land in the “pass” pile, or providing sustenance for an army of pedantic critics. Frustratingly, they are usually words you know how to spell, but somehow skimmed over in your rounds of editing. If we are our own harshest critics, why do we miss those annoying little details?

The reason typos get through isn’t because we’re stupid or careless, it’s because what we’re doing is actually very smart, explains psychologist Tom Stafford, who studies typos of the University of Sheffield in the UK. “When you’re writing, you’re trying to convey meaning. It’s a very high level task,” he said.

Stafford explains that the process of writing is like driving to a familiar place. Your brain knows the destination and generalizes the details so that you can focus on other things — like how you’re going to write the conclusion or how you’re going to tie the current sentence into the next paragraph. You may notice this process when you’re driving to work and realize that you don’t remember the last 10 miles. You were busy thinking about how you’re going to help Little Johnny discover the joys of reading. As long as everything is generally the same, your brain operates on instinct.

The author of the preceding article experienced this phenomenon when writing the story itself — he left out an entire paragraph! His brain knew where he was going, and failed to see that he’d missed a key point. In this case, his editor, who had not taken the journey, caught the mistake. He is not alone.

- Stop shaming people on the Internet for grammar mistakes. Its not there fault.

- What to do when someone corrects your grammar

The aforementioned publication is not the only one grappling with errors. Consider:

- Spelling, Grammar, and Scientific Publishing

- Public editor: Egregious grammatical errors caught by Globe readers

- Errors in the Constitution—Typographical and Congressional (It’s not online, but this example shows how long editors in our country have struggled with errors.)

Online publications differ in their correction policies

Major online publications have correction policies based on the admonishment by the Society of Professional Journalists to correct their errors. However, online publications — from bloggers to corporate owned media outlets — differ in their interpretation of what needs to be corrected and how much transparency is required of different types of corrections.

- Made a mistake? Advice for journalists on online corrections

- How to correct website and social media errors effectively

- The State of Online Corrections: News sites lag far behind print and broadcast outlets

- How journalists can do a better job of correcting errors on social media

Most online media publications have editors and other production workers who can find and report mistakes. They also have loyal readers who will kindly report errors, as well.

As an individual blogger, who also teaches, my editorial process is much shorter, and mostly involves me trying to find my errors. I correct minor grammatical errors, but add a note or use the strike-through when I correct any major grammatical errors or any factual errors. What I’ve discovered is that when I look at my writing after a few days, or in a different format, my mistakes jump out at me like a deer crossing a highway at dusk. My brain slams back to reality.

This explains why my readers notice my errors, even when I don’t. My readers have not taken this journey with me, so they’re staring out the windows noticing every detail. I discovered this the hard way back in the mid-90s when a reader called to tell me that my newspaper article would have been wonderful if I hadn’t used lead instead of led. While he was correct in that I had chosen the wrong verb, and my editor had missed it, his assertion that my error ruined the story said more about his level of pedantry than about my communication skills. (Not that pedantry itself is bad. We do want our architects, engineers, and mechanics to have a certain level of attention to details.)

Even the grammar police can’t agree

Of course, we can all agree that online publications will make errors, and that those errors don’t mean writers are stupid. We can also agree that writers and editors should correct their errors.

But what are errors? Not everyone agrees.

- The 20 Most Controversial Rules in the Grammar World

- English: the packrat’s dream

- The 9 Most Controversial Grammatical Rules

- Steven Pinker: 10 ‘grammar rules’ it’s OK to break (sometimes)

During my years as a newspaper reporter, I developed a thick skin regarding my writing. I also quickly discovered two methods for finding errors:

- Print out the article and read the hard copy. This would reset my brain and allow me to see my errors.

- Ask someone else to read it. My managing editor read my work, and I helped read hers. Our production people would also read over our work looking for the more obvious errors.

Even with this process, errors still crept through.

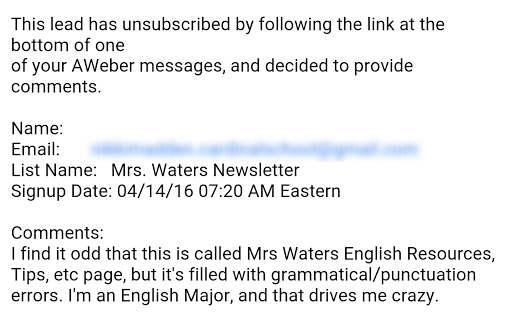

I tell you all of this because I received the following mailing list unsubscribe notice in my email when I rolled out of bed at 6:30 this morning:

As a writer, I appreciate readers who point out specific errors with the intention of helping me. If you see a mistake, feel free to hit the contact link above and point it out. Consider yourself deputized as editors for this publication.

That said, I’m going to tell you the same thing as I tell my students when we’re learning how to peer edit: Your purpose is to help the writer make their work better. Be specific, tell the writer what he can do to make his writing better, and no ad hominem attacks.

Which leads me to the most important question:

What are we teaching our students?

I have to assume that the former member of my mailing list who unsubscribed is a teacher. After all, why would he have subscribed in the first place, right?

I fear for the students of grammarian teachers. What attitude are we projecting to our students? Is our attitude teaching them that if you can’t write perfectly, then you shouldn’t even try? Are we judging their attempts to communicate based on the technicality of writing?

Yes, we should be teaching students how to use correct grammar. But grammar isn’t the end, it is the means. Grammar is the vehicle that carries our message. Yes, sometimes that vehicle has a flat tire, sometimes it’s got a little hail damage, and sometimes it looks like it’s been hit by a semi-truck. But we shouldn’t judge the message based on the grammar.

Are we judging our students’ messages based on their grammatical errors? I imagine teachers aren’t holding their students to the same standards as they do a fellow English teacher. However, students are sponges soaking up our attitudes without either of us really knowing it. They will know if you are silently judging them for their lack of “grade level” grammatical skill even if you don’t say it.

I have students who would rather stop writing and take a zero than make mistakes. I have students who think they are bad writers because they have not internalized the grammar rules yet.

We should think twice before we discourage a student, a fellow teacher, or any other human being from writing because that person is not perfect, and makes mistakes.

Consider the following:

- It is fortunate for us that Wilson Rawls didn’t let his lack of grammatical skills silence him.

- Perhaps our perception of errors is really just an artifact of dismantled Byzantine grammar empire.

- Why typos and spelling mistakes don’t really matter

- The Best (Worst?) Typos, Mistakes, and Correrctions of 2012

Why I’m am not a fan of grammar nazis grammar correction militia

Award-winning freelance writer Carol Tice states plainly why I teach my children and my students to craft their messages first and worrying about the mistakes later in the writing process:

I just had to look up the guy who unsubscribed from my Morning Motivations emails because of a perceived double negative, and discovered that he has a book on Amazon. A book with a flabby three-star average rating (out of five stars). And reviews calling the book “boring.”

With all the time he spent getting PO’d about my grammar, writing and sending me an email, and unsubscribing from my list, he could have improved his own writing by reading a writing blog, reading chapter of a book on the writing craft, or editing some of his own work.

I guarantee you will never see, say, Stephen King shooting off an email to a writer admonishing her for a typo. He’s too busy, you know, writing bestsellers.

What a waste of time. Tice also points out that grammar police have bad attitudes, struggle with their own writing, and aren’t perfect themselves. Instead of spreading negativity on the Internet, when you see an error, kindly point it out to the writer using a private communications method, like the contact form, and state the specific error you receive. I, as most writers, are grateful when our readers help us improve. As my managing editor said:

Writers are only as good as their editors.

I’ll add that writers and editors are only as good as their teachers. In the writing workshop advice of teacher, literacy coach, and author Penny Kittle:

…worry creates constipation. It’s not surprising that many students come to writing reluctantly — like dragging myself to the dentist, expecting distress. If we teach 10-year-olds or 18-year-olds that writing is about avoiding hazards, their fear will create dependence. Instead of producing writing that’s alive with confidence, they’ll ask for teacher guidance on every paragraph.

It’s time to stop scolding and start teaching.

As teachers, we should function more as coaches who guide our students to finding their voices as writers, and less as critics intent on stifling anyone who does not exhibit perfection.

In the words of Forbes.com contributor Rob Asghar:

Indeed, the rules for storytelling, interaction and engagement are far too different now for us to nitpick our way through other people’s writing. And so typos are on the rise everywhere, yet we’re surviving. Major news publications post articles quickly, without the benefit of a rigorous scrubbing. This is painful to classicists. But I sense we classicists are reactionaries, dinosaurs noisily drowning in the tar pits.

Don’t be a dinosaur. Our kids need you to rethink your grammar paradigm, to meet them where they are, encourage them to write, and then work with them as they polish the messages they have crafted. Need help? Sign up for our mailing list below!

This is a very brilliant view of grammar errors. I can say that when I was in primary and secondary schooling I had a strong fear of writing, especially when I knew my work would come back to me with squiggled red marks covering it no matter how much I worked to make it error free. I felt less willing to write a paper and developed a procrastinators habit since I felt it would not matter anyway how much time I spent on my paper. Having teachers that stressed correct grammar over anything else ruined writing for me and I want to be someone who is not going to continue on a need for grammar over content.

Anyway, I’m working my way to becoming an educator myself. I have a year left of school before I can have my own classroom. Is there any advice you would be willing to give to an upcoming educator?