9/12/22 Note: Author Shannon Dittemore saw our post on Instagram and offered to do a video call with your class! You can reach out to her on Instagram or her website.

Providing the following book review is Dr. Chea Parton, visiting assistant professor of Curriculum and Instruction in the Transition to Teaching Program at Purdue University. She is a former English teacher in rural Indiana and is working on publishing her book Country Teachers in City Schools: Negotiating Identity and Place. She is also author of the Literacy in Place website.

“What are fantasy books about? Kids from the sticks who become heroes. And when they get picked on or pitied for being from some District Twelve backwater, you root for them even harder. You know everyone who gives them crap will get karma in the end…Then, when the quest is over a lot of them go back to their villages, or districts, or wherever. And they’ve succeeded. How often do you see that in non-fantasy stories?” (Monica Roe, “Unhealthy Breakfast Club”, Rural Voices anthology, p. 14).

Many of the heroes that exist in fantasy — Katniss and Peeta; Frodo; Eragon — would’ve probably lived in rural places, trailers even, and that’s cool if it’s fantasy—even if in our society folks who live in trailers are often referred to as trash. Reading this story, I realized that I had never thought about rural places and people as fodder for fantastical hero stories. I’m still unpacking that — a different post for a different time.

For now, I want to think about the possibilities that exist in understanding our own world through the exploration of another. Truth told, I’m not much of a fantasy reader. I tend to gravitate toward gritty realistic books that thrust me into stories and issues of the world I know. I guess sometimes it feels like work to get to know a new world and keep everything straight—the new names of places, the creation stories, the peoples, their languages. But every now and again an opportunity presents itself for me to read outside my comfort zone, and I take it. Most of the time, and in this case, I’m glad that I did.

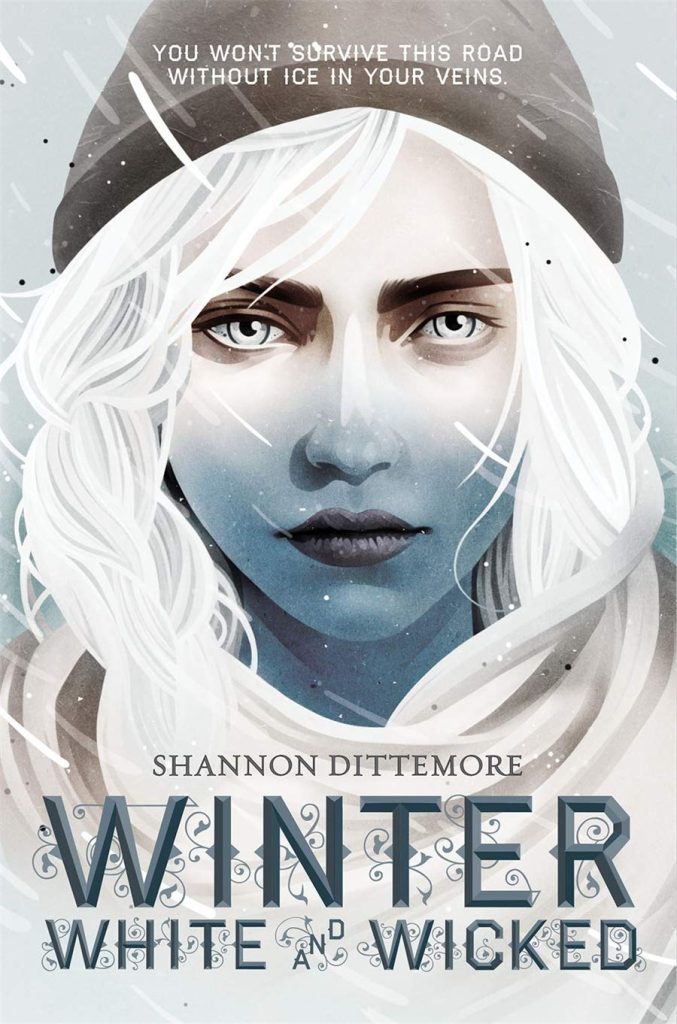

As part of my work with rural young adult literature, I’m a member of a committee that selects the winners of the Whippoorwill Book Award for Rural YA Literature, I get to read a lot of books and have wonderful conversations about their rural salience and potential for rural classrooms, teachers, and readers. As part of this award year’s submissions, we read Shannon Dittemore’s (2021) Winter White and Wicked. One look at the cover told me that it wasn’t my usual fare, but the cover was super cool and the story included ice-road trucking, so I was excited to get started.

Here’s the summary from the dust jacket:

Twice-orphaned Sylvi has chipped out a niche for herself on Layce, an island cursed by eternal winter. Alone in her truck, she takes comfort in two things: the solitude of the roads and the favor of Winter, an icy spirit who has protected her since she was a child.

Sylvi likes the road, where no one asks who her parents were or what she thinks of the rebels in the north. But when her best friend, Lenore, runs off with the rebels, Sylvi must make a haul too late in the season for a smuggler she wouldn’t normally work with, the infamous Mars Dresden.

Alongside his team — Hyla, a giant warrior woman, and Kyn, a boy with skin like stone — Sylvi will do whatever it takes to save her friend.

But when the time comes, she’ll have to choose: safety, anonymity, and the favor of Winter—or the future of the island she calls home.

While Layce is a fictional place, its people, structures, and economic systems reflect our own in ways that can open up deep conversations about what’s happening in our own world. Here are a few of the interesting takeaways for me that I would love to talk about with students.

Faith and Religion

There are various connections to the cosmology of Layce and the existence of Winter to other world religions and belief systems. Exploring how the role of religion and faith function for the people’s in the novel can help us think about the ways they shape our own world. Thinking about the correlations and connections between faith and religion and power can lead us to examine those in our own world.

Readers could ask:

- What do members of the various people groups believe about how their world came to be? How does it influence and shape their interactions with one another?

- What ideologies exist in opposition to one another? How does the text explore that tension and its impact on the people of the fictional world?

- How can we use these fictional tensions to better understand the tensions between belief systems in our world?

Racial Systems and History

There is a clear distinction drawn between the different peoples in this world. The Majority, the Shiv, the Kerce, and the Paradyians are all positioned differently within Layce society based on their connections to and/or distance from the gods of their creation. Because we read the word through our world, I found myself reading certain people groups as analogous to racialized groups in our own society. I don’t know whether or not that this was intentional on Dittemore’s part, but regardless it is possible and makes for an interesting discussion.

Readers could ask:

- Who do we see in these fictional peoples?

- What races do we imagine them to be and why?*

- How does the power dynamic we see at play among and between them speak to what we know of and experience in our own world?

There are also correlations to history and the teaching of history in that remembering is really important to the Shiv and Paradyians but the Kerce don’t see the point of it. With today’s white supramcist movements to suppress some of the most important and painful parts of our nation's history, this has the potential to open up conversations about the role of history in our understanding and knowledge of the world and ourselves.

* (And because these conversations can cause a stir and even cost schools accreditation in some states, maybe this fictional world is enough of a proxy for our own that those explicit connections don’t have to be made. Instead of asking students out-right to discuss the relationship between people groups on Layce or how they envision them in our own racialized systems, it could be enough just to ask them to think about how power moves among the peoples and characters in the fictional world. At the very least it would get them thinking about inequity tied to institutions and systems. It’s not Critical Race Theory (CRT), just characterization, and there has to be a standard that requires students to learn about that in every state regardless of anti-CRT stances.)

Economic Systems

I don’t think that it was a coincidence that people are mining Kol from the mountains on Layce for the Majority. This was one of the most striking connections for me—the depiction of a resource extraction community. All rural areas that have important resources have experienced being a resource extraction community. Whether it’s the move from slavery to sharecropping; from family to corporate farming, mining, fracking, drilling for oil, etc., rural people and places have long endured being made to work for someone else’s gain. In one scene, Sylvi and her crew come across some Rangers dousing Kol miners in Kol without protection, essentially killing them. Her description of them is haunting:

Kol miners lining the road to our left and right. Unlike those wandering the town center, looking for food and drink, these laborers clearly don’t have any standing with the Majority. They’re underfed and underclothed, likely indentured servants of lesser citizens who couldn’t find work elsewhere. Their coveralls are smeared head to toe in kol, black dust shimmering in Winter’s light. It’s not just the standard dusting that comes with the job either. This is intentional. Excessive. And dangerous. (p. 42)

Long-time and excessive exposure to kol could lead to hallucinations, madness, addiction, and death. Like the resource extraction communities in our own world, the extraction doesn’t benefit the miners.

Despite its hazardous nature, it’s our most valuable commodity. Kol is a mineral that amplifies things, makes them more than what they are. It’s used in all sorts of goods: cosmetics, medicine, petrol. But of all the islands on the Wethyrd Seas, it can be found solely in the mountains of Layce and, as such, only the Majority is allowed to mine it. They tell us it’s so the council can ensure the proceeds benefit all the islands under their control, not just a small smattering of mountain folk. Not just the ones digging it from the rock. (p. 43)

But because of the way the Majority has built systems on Layce, the miners continue to mine even when it kills. Kol and its relationship to larger societal forces on Layce all but beg to be used as a frame to examine the extraction processes and power dynamics that go with them in our own world. Not to mention their influence on climate change.

Readers could ask:

- How and where do we get our resources? Who benefits?

- What are the effects on the people and places those resources come from?

- How are the folks who actually do the extracting/cultivating of the resource viewed by society versus those that benefit from their extraction?

These are just a few of the important questions Winter White and Wicked raises. There are so many more connected to gender and class and equity. Overall, I think one of the most powerful things about this book is that it is fantasy, because it provides a bit of separation between Sylvi’s world and our own. It allows readers and teachers to discuss the problems of today through a buffer—almost addressing these issues as hypotheticals even though they’re not. Issues of race, religion, history, and economy often make for fraught discussions, so allowing students to discuss them by proxy still allows them the opportunity to be critical of the world in a way that supports their growth in discussing such challenging and charged topics with one another.