ChatGPT is only three weeks old and I’m already seeing teachers posting on Facebook or Twitter about turning students in for plagiarizing with the artificial intelligence writing tool. This is not a good place for us to be if we’re wanting to empower student writers.Enter your text here...

Since this software first showed up on my radar, I’ve shared some suggestions from the San Marcos Writing Project and insights from fellow business owners in my Facebook Group. I've also listened to the “Art-ificial Intelligence” episode of the Today, Explained podcast, which helped me understand how ChatGPT works. If you’re not already familiar with the debate surrounding this new tool, I also suggest reading the articles claiming that ChatGPT will end high school English and how it really will not.

I agree that plagiarism is a real problem, but it isn’t a new issue in education, and it’s not as cut-and-dried as English teachers tend to make it seem.

The issue of plagiarism, how we teaching students about it, and what we do once we “catch” someone plagiarizing is one that tripped me up more than 10 years ago during my very first year of teaching. My school had a zero tolerance policy stating that if a student plagiarized five or more words in a row, then they would be given a zero on the paper with no chance to make it up. I had one student, who’d earned an “A” in my class up until this last assignment, plagiarize an entire sentence from one of her sources. This sentence didn’t sound like anything else she’d written in the paper and that’s how I caught it. One quick run through CopyScape verified my suspicion and provided evidence. A zero on that assignment would drop the student’s grade to a “C.”

I didn’t feel right about any of this (the huge assignment at the end worth a grade-breaking number of points or giving students a zero for one one small problem — whether it was a mistake or intentional). The student had worked hard all year long. It was just one sentence. But the letter of our policy stated that she had to receive a zero. I talked to my mentor teacher, trying to find a way around this, and she assured me that she would give a zero if her seniors plagiarized. I felt my hands were tied. This is how I ended up on the phone with an irate (and rightfully so) parent.

It’s a full decade later, but I distinctly remember talking to my student about why she plagiarized. She said she just really liked that sentence, but wasn’t sure how to cite it, and thought it would be fine since it was just that one sentence. Clearly, I had not done a good enough job of teaching students how to cite their sources. Of course, as a brand new, alternatively certified teacher, I had no idea what I was doing, so I hadn’t given them enough opportunities to practice and make mistakes in a safe place. Which is exactly what high school should be — a safe place to try new writing skills and tools and learn how to use the properly.

Also during my first year, another student plagiarized an entire essay. He did end up receiving a zero, but I still felt bad about this, too. He was a student who had struggled all year long and I had no idea how to help him. He was receiving services at our school based on his IEP, but clearly this had not been enough. I realized from this experience that I needed to have students turn in evidence of their prewriting and more drafts—not so that I could rank and sort them for a grade, but so I could find out who was struggling and help them succeed.

A few years later, a student turned in a poem she had copied from the internet. I instantly knew it wasn’t hers because it didn’t sound anything like what she had written before. So I found the source, showed it to her and asked her why. She said that she doesn’t usually write poetry and that should couldn’t think of anything good. She was not confident in her ability to write a poem.

So we went back to her quickwrite notebook where she had written down her thoughts on the topic she’d chosen. I told her to circle some of the phrases from that quickwrite and place them on their own lines. Boom! With some tweaks, she had a poem that followed the structure I’d given the students. She was amazed at how easy that was and I was able to talk with her about asking for help instead of just grabbing something off the internet.

Consider ChatGPT a conversation starter

Instead of viewing ChatGPT and other online tools as contraband, or waiting until someone has misused it and disciplining them, let’s use these tools as an opportunity to learn with students. Think of it like this: ChatGPT is to writing what Wikipedia is to research. You can’t use either resources and then just stop. In the case of Wikipedia, you can use the resource to develop background knowledge and then the references section to find some of the primary and secondary sources you can actually cite in your paper. Those sources (or a search through Google Scholar) can help you find scholarly, peer-reviewed resources. Similarly, ChatGPT can use used as a starting point. So let’s talk about what’s appropriate and what’s not in the various contexts students may face.

This is especially important with ChatGPT and other AI creators since you’re not going to be able to find the source online like you can when someone copies paragraphs from a webpage.

Assuming we’ve actually had discussions and workshops in class about plagiarism, why it’s unethical, and how to avoid it, we should view each incident we discover as either a mistake, or a cry for help. While it is true that some students don’t think cheating is bad (even though plagiarism can get you fired or kicked out of college), who are just chasing the grade and don’t care how they get it, I suggest we don’t assume that mindset of everyone. Claudia Swisher, a National Board for Professional Teaching Standards trainer, suggested that we work all year long on building trust between ourselves and students and lines of communication. Students need to know that they can trust us to help them when they don’t know how to write—that it’s worth it to communicate with us and not just hire their tutors, an online essay mill, the really smart kid in the front row, or ChatGPT to write that essay. We learned from the pandemic that flexible deadlines and strong communication with parents go a long way in helping students succeed and that is still true.

Start by exploring the history of ghostwriting and copywriting

Like most issues in education, plagiarism and copyright infringement aren’t as simple as one might initially believe. In both the the business and literary worlds, there is much more gray area than in the academic world and we’re doing students a disservice by not addressing these areas. Students need to understand the concepts of ghostwriting, copywriting, and private label rights (PLR) both in the literary and business worlds, and how they apply (or not) to academic writing.

Ghostwriting

If students don’t know what ghostwriting is, they’re bound to be confused when they find out that Peter Lerangis (and others) ghostwrote many of the books in The Baby-Sitters Club series after the original author, Ann. M. Martin decided to take a break. Martin estimated that she wrote between 60 and 80 of the 213 novel series. Also, Scholastic Corp. claimed that some of R.L.Stine’s Goosebumps books may have been ghostwritten. More transparently, the Nancy Drew Diaries and Sweet Valley High series were extensively ghostwritten. If famous authors of some of their favorite books can hire others to write, why can’t students?

Ghostwriting isn’t new or limited to fiction, either. Writers have been creating content for other people’s use for centuries. Count Franz von Walsegg, an Austrian aristocrat, liked to commission famous composers of his time to write musical compositions for him. He is most famously known for hiring Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart in 1791 to ghostwrite a requiem mass for his late wife. Even some of the books in our literary canon were ghostwritten — think of The Count of Monte Cristo, who we’re told was written by 19th century French novelist Alexandre Dumas. Except that Auguste Maquet is now believed to have ghostwritten that novel, The Three Musketeers, and several other stories with Dumas before ending their partnership and starting his own solo writing career. More recently, there been some discussion and debate about the use of ghostwriters in the rap music industry—a gig that can pay tens of thousands of dollars to the talented writers.

Outside of literary content, politicians often hire speech writers to craft the messages they share with the public and ghostwriters to draft their autobiographies —and other messages. For example, Ronald Reagan's autobiography, An American Life, was largely ghost written by Robert Lindsey, a prolific New York Times journalist who also write true crime books. Celebrities even hire ghostwriters, including George Takei, who hired a comedian to help him produce content for his popular Facebook page.

Copywriting

In the business world, companies often hire copywriters to write text (copy) for their advertising and marketing campaigns. Jingle lyrics, sales letters, website articles, television and radio commercial scripts are all written by hired copywriters who are not named as authors of the pieces, as they are written on a work for hire basis, which means the copyright is owned by the employer, not the author. (Oklahomans, your favorite jingle was not written by Paul Mead or B.C. Clark.)

Copywriters can charge hundreds, if not thousands of dollars for their work, which is a price tag that’s out of reach for most small businesses. So entrepreneurs developed a new type of licensing: Private Label Rights, also referred to as PLR.

Private Label Rights

In the entrepreneurial world of internet marketing, it is common practice for small business owners to purchase and use PLR articles or royalty-free images. In both of those cases, business owners or their virtual assistants purchase a license to use articles or images for specific purposes without attribution. Business owners or their VAs then rebrand and personalized the content to suit the business and its audience. For example, most of the images on reThink ELA are ones for which I’ve purchased a license and then I add my headline and watermark so they can serve as visually appealing illustrations for my articles. (Naturally, one still has to be careful to purchase PLR licenses from reputable companies and vet them for quality.)

On my business website, I’ve frequently started a blog post or special report with a PLR article I purchase (from someone who I’ve known for decades) that contains the basic information I want to convey, such a list of how to do something, and then added my own personal experiences as illustrations, advice I’ve gleaned from my years of experience, and additional resources my readers might need. Several of my entrepreneurial colleagues run businesses that sell bundles of articles they (or their contractors) have written to help their customers save time. Instead of spending hours writing articles to educate their own audiences, they can focus on the work that earns them their income. Some of these PLR businesses have earned millions of dollars writing bundles of articles on a specific topic, like baking, and then selling licenses to use those articles without attribution for a very reasonable price. In the business world, this is both legal and ethical. It’s considered a smart way to outsource a task that could take a huge amount of time away from a business owner who needs to be doing what actually earns them money.

So what does this mean for English teachers and their students? And what can we do to prepare students for not only the continual evolution of AI technology, but the expectations of the business world?

Introduce students to ChatGPT ASAP

We also shouldn’t wait for students to discover and misuse the tool before we introduce it. Instead, we should show students how to use the tool appropriately (just like with Wikipedia). Inc. Magazine published an article about how to use the AI tool in your workflow. The article suggests using it to:

This is how we can teach students to use AI writing and other online tools — as a starting point for their own work. Below are some steps you can take in your classroom to introduce students to ChatGPT, the complexities of plagiarism and copyright, and how to use to use online tools appropriately.

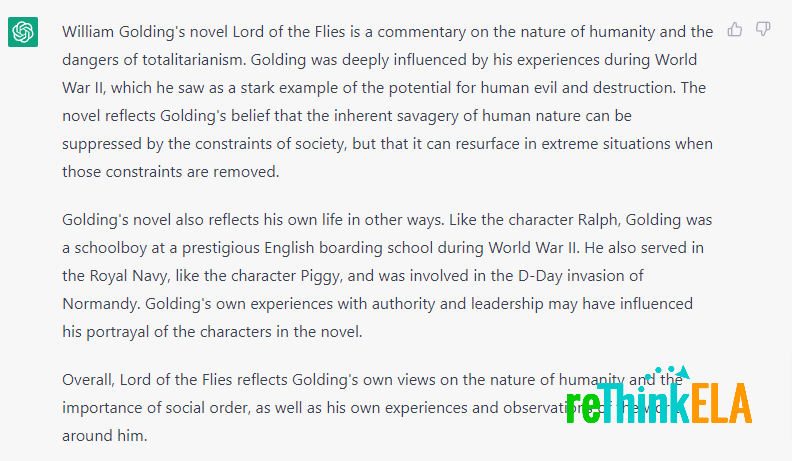

Use ChatGPT yourself to generate a response

Whether you’ve already written a prompt or you’re in the process of developing one, enter that prompt into ChatGPT. I borrowed an assignment that a former student provided to me and created a one-sentence prompt from the single-space, double-sided assignment instructions: How does William Golding's Lord of the Flies reflect aspects of his world and life?

This is what ChatGPT provided:

Not a bad start — but clearly not what I’m looking for. So I tried again: Write an essay about how Lord of the Flies reflects aspects of Golding's world and life. The essay must contain 10 quotes from the novel and 10 quotes or paraphrases from peer reviewed sources.

This time, I did get more, but still not a full-blown essay (and there are some other problems with the information, most notably the timing):

Not only will this help you create a better prompt, but will also help you familiarize yourself with the type of content an AI writer will produce in response to it.

Use AI writers to create mentor texts

Once you have created your prompt and a reasonable mentor text, it’s time to share with your students. Open ChatGPT on your interactive board and enter your prompt. Then let the students watch the system generate a response. Immediately, you’ve taken away the thrill of ill-gotten gains—and showed students you’re in touch with current technology. It’s a win-win.

Follow this up with a discussion of what students notice about the writing. What makes this an example of good writing? What is missing that could be added to improve the model?

If students seem quiet, put them in groups of two to four and have them write down three things they notice that make this text an example of “good” writing and three things they notice are missing.

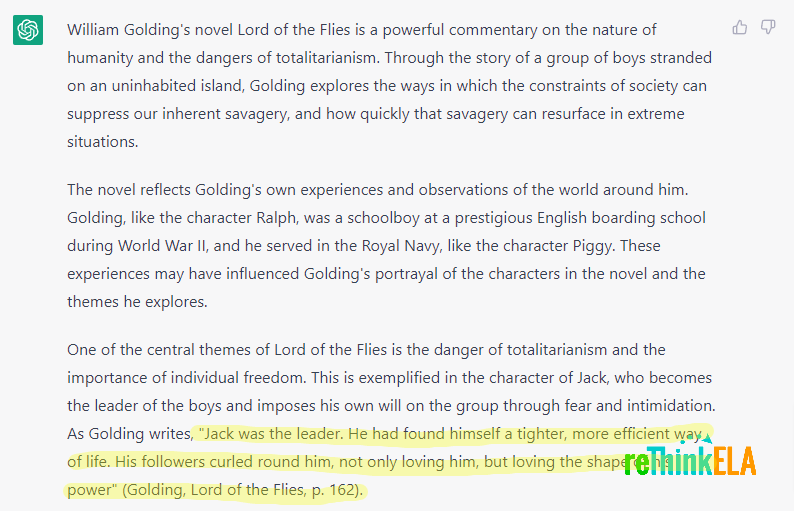

Also, ask them how you could change the prompt so that it would require students’ own personal experiences, either from within the class or from their life-experiences outside of class. Taking my own advice, I entered the following into ChatGPT: Write an essay about how you identify with the experiences William Golding wrote about in Lord of the Flies based on the modern world and your life. The essay must contain 10 quotes from the novel.

This is what the AI writer generated:

As a reader in the modern world, I can identify with the experiences and themes that William Golding writes about in Lord of the Flies. Despite being set on an uninhabited island, the novel feels relevant and relatable to my own life and the world around me.

One of the themes that I particularly identify with is the danger of totalitarianism and the importance of individual freedom. In the novel, the character Jack becomes the leader of the boys and imposes his own will on the group through fear and intimidation. As Golding writes, "Jack was the leader. He had found himself a tighter, more efficient way of life. His followers curled round him, not only loving him, but loving the shape of his power" (Golding, Lord of the Flies, p. 162).

This theme is something that I can see reflected in the modern world, where authoritarian leaders often rise to power and seek to control and suppress the freedoms of their citizens. The importance of individual freedom and the dangers of totalitarianism are issues that I feel strongly about, and I can see how Golding's novel speaks to these concerns.

Another theme in the novel that I identify with is the role of language and communication in maintaining social order. The character Piggy, who represents intelligence and reason, is ostracized and eventually killed because he is unable to communicate effectively with the other boys. As Golding writes, "Piggy's glasses were the glass that protected him, and the thing that made him different was his glasses. They were a sign of difference, and the boys knew it and Piggy knew it" (Golding, Lord of the Flies, p. 111).

This theme is something that I can see reflected in my own life and the world around me. In today's increasingly interconnected and globalized world, the ability to communicate effectively across language and cultural barriers is more important than ever. At the same time, the spread of misinformation and propaganda through social media and other channels highlights the importance of critical thinking and the need to be able to discern fact from fiction.

Overall, Lord of the Flies is a novel that speaks to universal themes and experiences that are still relevant today. The dangers of totalitarianism, the importance of individual freedom, and the role of language and communication are all issues that I can identify with and see reflected in the modern world. Golding's novel serves as a powerful reminder of the inherent savagery of human nature and the ways in which it can be suppressed by the constraints of society.

While this is a well-organized start, I already see that the software didn’t actually include any personal life details. If students are going to write about the theme of world leaders suppressing freedoms, what personal experiences can they share to help the reader see how this is happening today? If the student is writing about how language and communication can be used to maintain social order, what examples can students give from their own lives—either in school or outside of school?

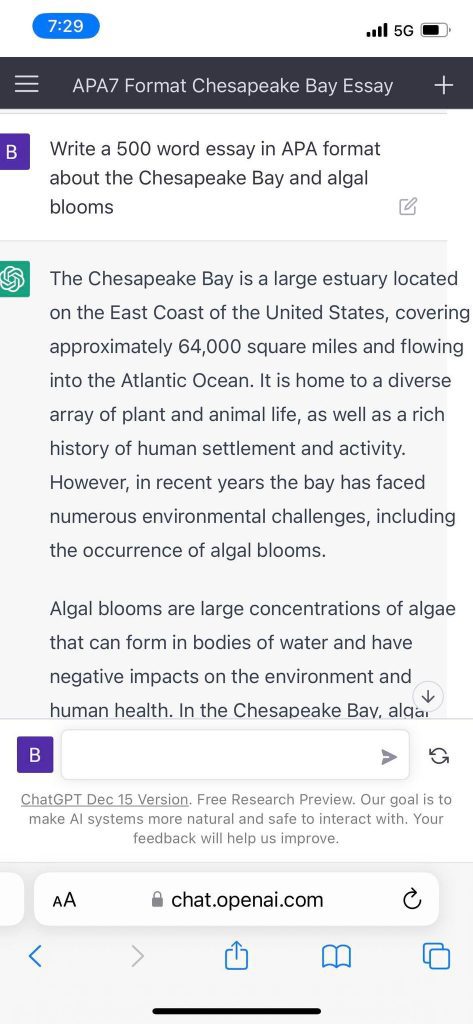

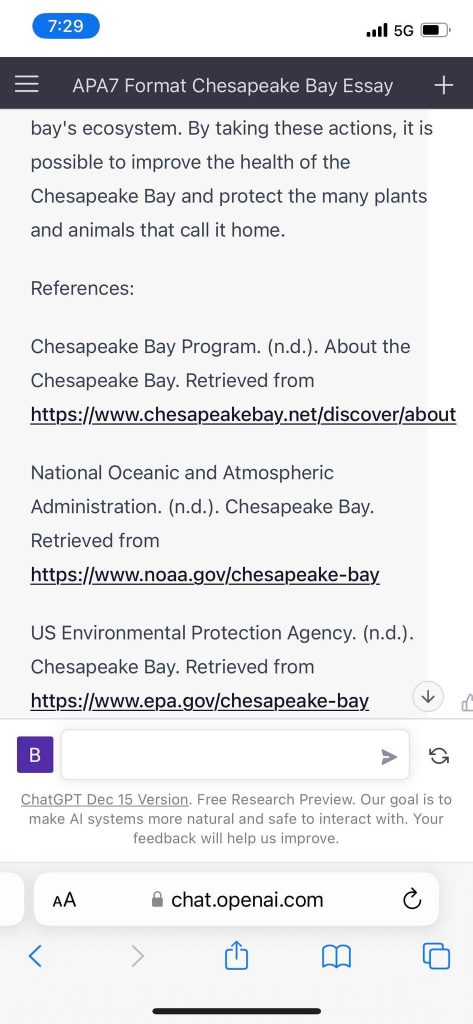

Dr. Becki Maldonado, a 9th grade teacher at Parkside High School in Salisbury, MD, took this exercise a few steps further during a late-night Facebook chat and then write about the patterns she noticed while generating an essay in response to the prompt: "Write a 500 word essay about the Chesapeake Bay and algal blooms." She then modified to instruct the generator to write the essay in APA style.

(Screenshots by Dr. Becki Maldonado show what ChatGPT generated in response to her prompt.)

Dr. Maldonado noticed that not only does the AI writer generate very short paragraphs, but it also created bogus citations. If you try to follow the links that the image shows, they go to pages that don't exist. I see that it also did not accurately duplicate APA 7 style, since you no longer need to use "retrieved from" before a website address.

Dr. Maldonado then tried generating a short story about a robot. She noticed after asking ChatGPT to generate the story twice, it chose the same name for the robot both times. Her experiments further proved what she has been reading in LikeWar: The Weaponization of Social Media by P. W. Singer and Emerson T. Brooking. Dr. Maldonado wrote:

Even in AI there are patterns in speech, like when I asked it to write a story about a robot, in both stories the robots name was Max. Also when I asked it numerous ways to write an essay in APA format about the Chesapeake Bay, all the essays had certain things in common:

- They were written on a 7th grade level.

- No grammatical mistakes.

- All paragraphs were 2-3 sentences long.

- Only general knowledge.

- No specific details given.

- No direct quotes.

- No in-text citations

- Bogus references that when clicking on the link, the page could not be found.

ChatGPT is just another bot that when you know the patterns it is easy to recognize text generated by it.

Dr. Aimée Myers, assistant professor of curriculum and instruction at Texas Woman’s University, explored incorporating ChatGPT into her teacher education courses. She wrote a few of her own observations about the AI writer:

- It makes stuff up when it doesn't know an answer, including creating bogus citations, which Dr. Maldonado also noted.

- It doesn't know anything beyond 2021, which means that teachers minimize it's usage by creating writing prompts that are timely and relevant.

- It can't write reflections or metacognitive responses, so incorporating these kinds of prompts in your assignments will require students to develop their own texts.

- It cannot synthesize classroom texts with visual materials.

- It cannot create multimodal assignments like infographics and digital essays.

- It can't make predictions about the future or respond to "what if" scenarios.

- It can't synthesize lived experience with course content. So asking students how their life experiences influenced their interpretation of a canonical novel is better than asking how the long-dead author's life influenced the novel.

- It cannot create essays or reports from primary empirical data collected by the students.

...it’s almost like an evil genius educator created this to force other educators into using more culturally relevant pedagogy, multimodal curriculum, and higher order thinking. I think I’m in love, Dr. Myers wrote.

Discuss the results with your students

Perhaps give students time to read and annotate their AI-generated responses. Have them write down the questions they have about the AI writer’s craft. Again, this is something they can do as a group and then write their questions on the board or in a shared Google Doc.

Also, if ChatGPT has taken a particular side, or argued a specific point, ask students to write the opposite viewpoint. For example, in an essay about Lord of the Flies, a student might disagree with the whole premise that if left to their own devices, leadership will devolve into totalitarianism. Sources they could use for a more hopeful view of human nature to stand against Golding's might include the story about a real shipwreck and what actually happened.

Swisher suggested asking each student to generate something on the same topic with their own devices and then compare and contrast. If the AI generated the same thing for everyone, how can students modify the prompt to generate a better response — and then how can they take that model and make it their own?

Again, these questions and the ones generated by students can be discussed in class along with the issues of how they can use the AI as a brainstorming and outlining tool as part of the process of creating their own writing. (Of course, I also suggest showing them sites like Originality.ai, GPT-2 Output Detector Demo, or AI Content Detector. Not only will they know that their originality can be verified, but they can run it through the system themselves if they aren’t sure. And for purely academic writing, like research papers that need to be heavily cited, I recommend introducing students to the Purdue Owl Research and Citations Resources and teach them how to accurately use citations generators like Easy Bib or Citation Machine.

Instead of fighting the advent of AI technology and finding new and creative reasons to rank and sort students, let’s focus on teaching students ethical and appropriate ways to use the tools at their disposal and focus on empowering the writers in our classrooms.

Additional AI Writing Resources

- 1/9/2023 - "A college student created an app that can tell whether AI wrote an essay" by NPR. Discuss with students how there is more than one AI writer -- that ChatGPT is just one software amongst several free and paid versions. You might even try generating an essay and running it through the detector to see what score it gets. Then modifying the text by adding your own narrative, insights, and expertise and run it through the detector again to see how it is scored. I did this with an blog post I generated with ChatGPT. On the first run, the detector said that the post was likely generated by AI. After I modified the post though with my own experiences and insights, the detector's response was that the post was most likely written by a human.

Michelle, I love this view of how to deal with GPT and other technologies like it. Thank you for your fresh perspective!

Thank you, Stephanie! I’ll continue updating this article as I discover more strategies and as the technology evolves.