During a Leadership Academy I attended recently, we talked about what motivates teachers. Our presenter, Dr. Bobby Moore, shared with us the work of Daniel Pink, who postulated that there are 3 factors that lead to better work performance and also to personal satisfaction. Dr. Moore also threw in a fourth factor. Those factors are:

During a Leadership Academy I attended recently, we talked about what motivates teachers. Our presenter, Dr. Bobby Moore, shared with us the work of Daniel Pink, who postulated that there are 3 factors that lead to better work performance and also to personal satisfaction. Dr. Moore also threw in a fourth factor. Those factors are:

Autonomy — This is our desire to be self-directed. Teachers who are motivated predominately by autonomy will not perform well under an administration that micromanages, or in a system in which the government wants to script every detail of their teaching practice. Studies of what motivates people, including the one I reference below, show that people are more engaged when they are allowed to be self-directed. Basically, these studies show this: If you want people to be innovative and creative, GET OUT OF THEIR WAY! As a brand new teacher (only 4 years experience), I’m not a stickler for autonomy. I do want to be able to do what I know is right for my students, but I don’t have a problem with people offering me direction, particularly when I need it. Perhaps when I move towards being a veteran teacher, this will become more important to me.

Mastery — This is our desire to get better at what we do. This is the main factor that motivates me. If I’m going to do something, I want to do it right, I want to be excellent, and I want recognition for that excellence. You can’t reward me monetarily for achieving mastery. As a matter of fact, I’d find it rather insulting if you tried to do so. Additionally, I’d be uncomfortable if you based my mastery on something like a student’s test scores, which I can’t control ultimately, while at the same time punishing another teacher who worked just as hard, but who had students who didn’t score as well. On the flip side of that coin, what if I become the best teacher I can possibly be, receive highly effective and superior scores on the qualitative portion of my teacher evaluation, but my students still don’t test well? I’ve poured my heart and soul into my teaching practice, and then you’re going to tell me I’m a bad teacher?! This will be especially true for teachers who work in high poverty areas where students are struggling with extreme poverty, resulting in absenteeism, lack of motivation, and inappropriate behavior. Oklahoma Middle School Principal of the Year Rob Miller of Jenks shares the story of Dr. Denise Gordon, a Texas science teacher whose mastery of her teaching practice is being denied by her administration. Dr. Gordon states:

I write this short essay to disclose what is happening within my own science classroom, I write to expose the demeaning work environment that I and my fellow colleagues must endure, and I write to give purpose to my years of acquiring the necessary skills and knowledge in teaching science for the secondary student. I am not a failure; however, by the Texas STAAR standard assessment test, I am since this past year I had a 32% failure rate from my 8th grade students in April, 2014. The year before, my students had an 82% passing rate.

Will teachers work towards mastery without a carrot and stick? If the studies I reference below don’t convince you, consider these open-source projects that were built by people working as many as 20-30 hours a week FOR FREE: Linux, osCommerce, Apache, Wikipedia, MySQL, PHP, Moodle, and The GIMP. As a teacher, I will work towards mastery because I have a purpose…

Purpose — This is knowing that what I do matters. Recent research in business shows that companies that have a transcendent purpose are more successful and attract more talented employees. Think Skype, Apple According to the author of the video below:

When the profit motive gets unmoored from the purpose motive, bad things happen (like bad customer service, shoddy products)… Companies that are flourishing are animated by their purpose… The big takeaway here is that if we start treating people like people… if get past this kind of ideology of carrots and sticks, and look at the science, I think we can actually build organizations and work lives that make us better off and make our world a little bit better.

So why aren’t we doing and teaching this in our schools? That said, I think we ARE doing this in my school. But what happens when VAM catches up with us? What happens when the current administration at my school retires? I want to be excellent at what I do, and I want to know that I’m making a difference in the lives of students, even if that difference doesn’t show up for 20 years, and only in the life of one student.

Belonging –This is being a part of a small family. I am blessed to have been a part of two educational families — at my current and previous schools. If my administration listens to me, empowers me to be the best I can be, treats me with respect, and values my opinions, than I will do my best work. This was never more clear to me than when I worked at a newspaper. I worked in the editorial department under the leadership of the managing editor. My husband worked in the press room, under the leadership of the publisher. My editor’s philosophy was to groom reporters and editors to do their best work. We were self-directed, with his guidance, encouraged to become the best journalists we could be, and recognized at the state and national levels for our accomplishments. For the record, I only made $18,000 a year at that job, but I was happy. On the other hand, my husband made $7,000 a year more than I did, but he was miserable. Why? Because the publisher operated the press room under the theory that employees work best when they’re mad — or so it seemed. He changed their hours with minimal notice, ignored their concerns about safety issues, and micromanaged his best employees (while at the same time letting others get away with ditching work for weeks at a time with no warning). When school administrators — or the government — starts trying to motivate teachers with carrots and sticks, they are going to lose their best assets. I don’t want to be lost.

What motivates teachers?

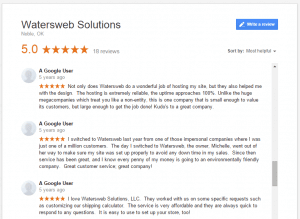

The above video references a study by Massachusetts Institute of Technology, in which economists gave students tasks to complete, and their performance was encouraged by a tiered set of rewards. In other words, those that performed really well received a large sum of money and those that didn’t do as well received only a small reward. This is like the motivation scheme you see at a car dealership. Those who sell the most cars receive the most commissions and bonuses. What did the scientists discover? As long as the tasks only required mechanical or physical skills, the rewards system worked as expected. Higher pay = better performance. Surprisingly (or not!), this reward system broke down as soon as the tasks required even rudimentary cognitive skills. When tasks require some conceptual, creative thinking, larger rewards = poorer performance! Apparently, these results have been replicated in other countries, and in studies done by psychologists, sociologists, and other economists. It’s not a fluke. What does this mean for our education system? Well, teaching is one of the most cognitively demanding, creative, conceptual acts one can engage in. Teaching demands that those who wish to be excellent at this endeavor excel in many different areas, from managing a room of rambunctious children to designing effective lessons and enrichment activities. For that matter, teaching is also like running your own business, which I did for almost 10 years (until I realized I liked teaching more than tech support). I built my business on the principles of “coopetition.” I worked with my colleagues and competitors for the betterment of us all, in the service of the customers, who were also members of our global social group. I stayed up late, and worked hard, to provide the best service possible for my customers. The results? Reviews like these:  If we want to keep our best teachers, we need to bury the carrots and sticks, and start listening to motivational leaders like Daniel Pink. I hope this happens, because I know I’m supposed to be a teacher, and I want to be the best teacher I can be, and have a positive impact on students for years to come.

If we want to keep our best teachers, we need to bury the carrots and sticks, and start listening to motivational leaders like Daniel Pink. I hope this happens, because I know I’m supposed to be a teacher, and I want to be the best teacher I can be, and have a positive impact on students for years to come.